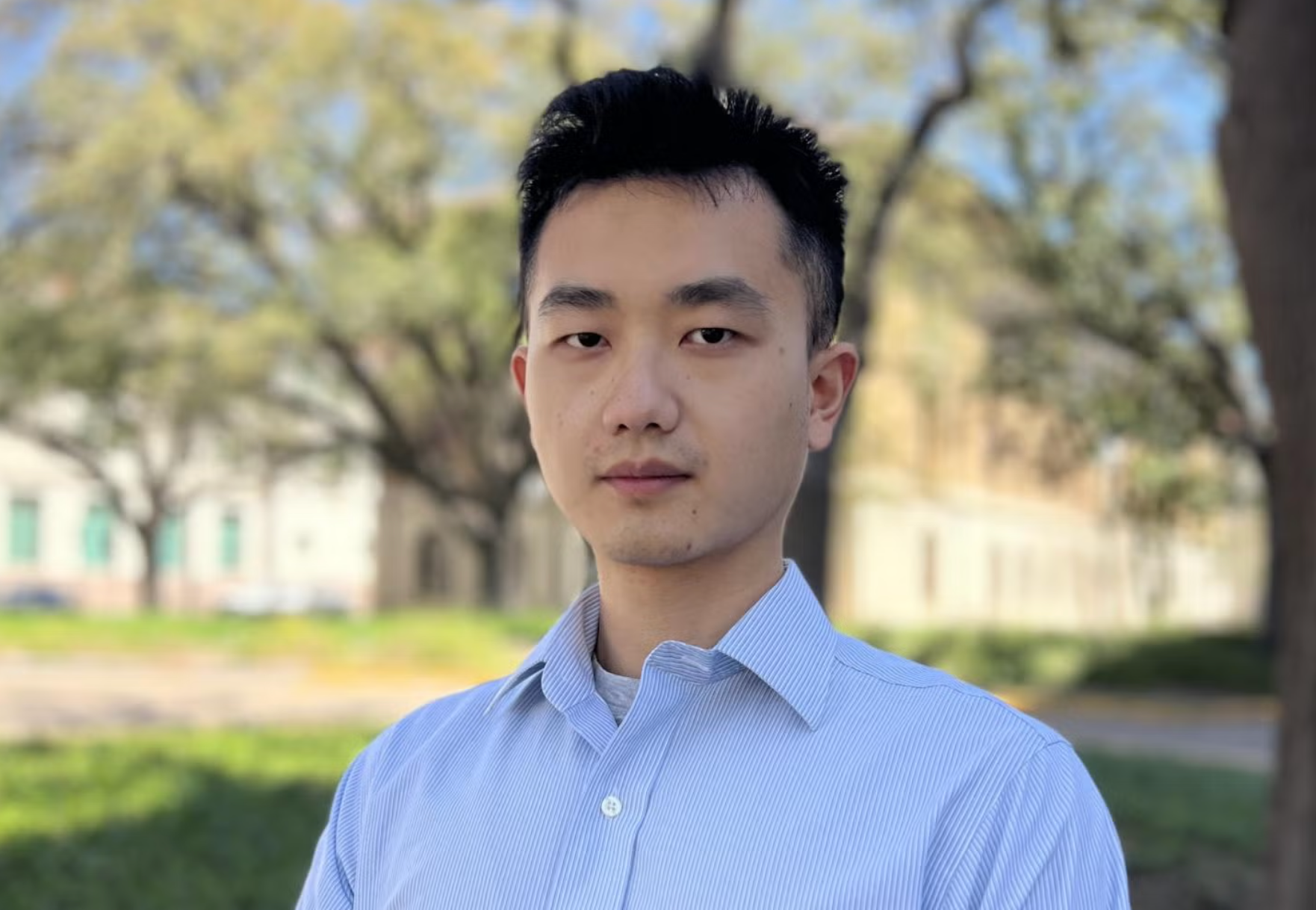

As record-breaking floods devastate communities from China to Texas, a new CU Boulder professor is working to harness the power of artificial intelligence to help vulnerable populations better prepare for these disasters. Dr. Zhi Li, who recently completed a postdoctoral fellowship at Stanford, is launching the Flood Lab at CU Boulder with a mission to reduce flood loss through fast, accessible, and tailored flood prediction tools.

In this interview with Colorado AI News, Li explains his vision for AI-powered flood modeling, why current systems often fail to protect people, and how new technology can help deliver the right warnings to the right people at the right time. He also discusses the importance of open data, community collaboration, and how AI tools can empower even non-experts to participate in emergency preparedness.

Li spent the last two years as a postdoc at Stanford University, and as much as he enjoyed Palo Alto, he’s also clearly excited about the new opportunities open to him at CU Boulder. He officially starts at CU in August and won't begin teaching until spring 2026, giving him the fall semester to focus on research and prepare for his new role in the classroom.

1. What are the goals of your Flood Lab?

"The whole philosophy of the Flood Lab at CU Boulder is to mitigate flood loss and help prepare people to combat those flood risks that happen every year, everywhere in the world," said Li. The lab is built around three core pillars that Li describes as modeling, data integration, and communication.

The first pillar focuses on improving how we simulate flood events using both physical models and AI to speed up the modeling process. Li explained that he was a flood modeler during his Ph.D. research, building traditional flood models, and he is now working with AI to reduce simulation time.

The second pillar emphasizes integrating data from remote sensing, ground observations, and social scientists to calibrate and make models more accurate so results will be tailored to communities at risk.

The third pillar addresses what Li sees as a critical gap: risk communication to help people understand and act on flood warnings.

2. How does your AI flood model work, and what sets it apart?

"Floods occur very rapidly. For example, in the flash flood earlier this month in Texas, the water level rose 20 feet in one hour. That's incredible. So, we need faster tools to simulate the consequence of flooding," Li explained. His approach combines traditional flood models with AI to dramatically reduce computational time, while maintaining accuracy.

Traditional flood modeling faces enormous computational challenges. When FEMA conducted surveys for 100-year flood plains across the country, "it took over a decade and cost billions of dollars – 10 billion dollars – to do that. It's just incredibly high computational cost," Li noted.

His AI-powered approach offers a potential solution. "What we have is an AI-powered flood model so that we can really reduce the computational cost while maintaining the same laws of physics.”

Li’s model can predict floods at one-meter spatial resolution, meaning people can identify exactly which properties or streets might flood and make real-time decisions about where to seek safety.

3. What specific technologies are you using to enable one-meter flood mapping?

Li's model relies on two critical data inputs. "The most critical input to the model is the rainfall from the National Weather Service. Number two is terrain data," he explained.

For rainfall data, he's optimistic about recent developments. "There have been a lot of advancements because of AI, and because of the big, mega tech companies like Google, Nvidia, and Microsoft. They release their own weather models," he said.

When it comes to terrain data, Li draws upon high-resolution maps available from the U.S. Geological Survey. "They have one-meter terrain maps. So, I can easily just download the maps and do the analysis for every county in the United States," he said.

However, this high-resolution terrain data isn't available globally. "Other places in the world may not be so fortunate to have such high-resolution data," Li acknowledged. To address this gap, he is exploring remote sensing solutions.

"There's been an effort to use remote sensing data to create very high-resolution terrain for anywhere in the world." He notes, however, that these approaches still need validation against ground observations.

His team has experimented with some international partnerships – they worked with officials in Medellín, Colombia, who were able to provide one-meter terrain data for a demonstration project.

Here in the U.S., Li has already created high-resolution risk maps for multiple locations, including San Francisco, Los Angeles, Orange County, and parts of Florida and Texas. These maps categorize risk from nuisance flooding (as little as 0.1 meters) to major events exceeding two meters.

4. Why do flood warnings often fail to protect people?

Li sees communication as a fundamental problem in current flood warning systems. Referring to the recent Texas flash flood, he said: "I think the forecast was there, and the warnings were there, but why didn’t people take action? The key missing part was communication."

He believes current systems are too generic and fail to provide actionable guidance. "I think the current National Weather Service could do better in terms of having customized warning messages to specific groups of people to guide them where they should go, and what will be the specific consequences of this flood, instead of just the vulnerable region for the county. The messages need to be customized and specific."

To this point, Li's research focuses on developing more targeted, personalized alerts that can reach specific, at-risk populations with appropriate guidance for their particular locations and circumstances.

5. Can AI also help personalize flood alerts based not only on where people live, but on what kind of special needs they may have?

Li is actively working on this challenge, integrating social and demographic data into his warning systems. He recently submitted a proposal to build what he calls an "AI flash flood forecaster" that would use artificial intelligence agents to work alongside human forecasters.

The system would incorporate data from the American Community Survey, which Li explained is an annual production of the U.S. Census Bureau that provides detailed social and demographic information "for each land tract of U.S. regarding social status, race, language, housing, and transportation."

"By integrating that information into our model, we can do more tailored messages. Instead of just having a centralized, county-level overall assessment, we can really push the notification for each user group that is at higher risk," Li said.

6. You're also working on an AI-powered assistant to help communities run their own flood models. What can you tell us about that?

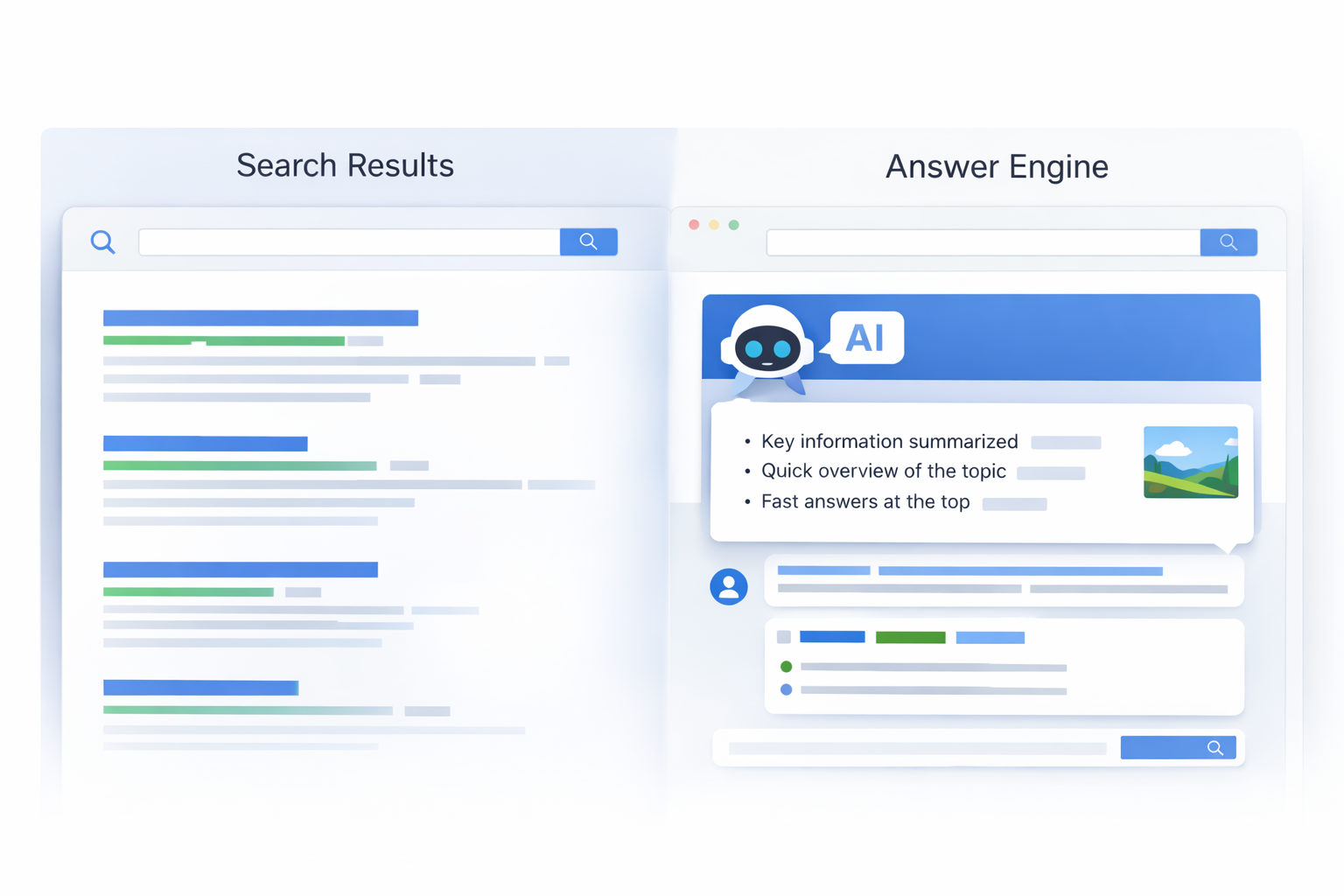

Li is developing what he calls an "agentic framework" to democratize access to flood modeling. "Instead of relying on a hydrological modeler to set up a flood model, any person, any lay person, can just talk to the LLM like ChatGPT. In the backend, it just sets up the physical model, and it then produces more reliable and interpretable results for the user," he explained.

This approach aims to remove technical barriers that currently limit flood modeling to experts. "I think that's one way we can remove the barrier for any lay person to understand the top-notch technology, and also the modeling, so they can do some flood models themselves, instead of relying on the public agencies like the National Weather Service to issue these warnings."

Li sees this as crucial for empowering local communities to understand and prepare for flood risks without waiting for official warnings or having technical expertise.

7. How do you plan to make your work available to others?

"I'm a strong advocate for open science and open data," Li said. He plans to publish his one-meter resolution flood model this fall and make it accessible through his website so others can use it.

Li is also developing a visualization platform where users can explore flood risk maps by region and severity. The platform will eventually include real-time alerts and interactive simulations to help communities better understand their flood risks.

8. How does CU Boulder – and Colorado more broadly – fit into your vision?

Li sees Boulder as an ideal location for his research. During the interview, he expressed enthusiasm about the local ecosystem, mentioning Boulder's strong environmental science community and emerging AI capabilities, as well as proximity to national research centers.

He's also excited about potential collaborations with local tech companies and the broader community interested in using AI for beneficial purposes.

9. What are you hoping for in terms of collaboration or support?

Li emphasized that achieving his ambitious goals will require collaborative effort and support. "It's going to take more than my own effort to reach such a goal, right? So, if any readers of Colorado AI News would be interested in collaborating or funding my research, that'd be fantastic, because we do need some brilliant minds to work together to combat that."

Li is currently recruiting a postdoc researcher for this fall, and Ph.D. students for Spring 2026. Looking ahead, he wants to build a team that's not only technically strong but also passionate about making real-world impact.

To learn more about Li's work or explore collaborative opportunities, visit the website for his Flood Lab at CU Boulder or his profile on the website of CU Boulder’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.