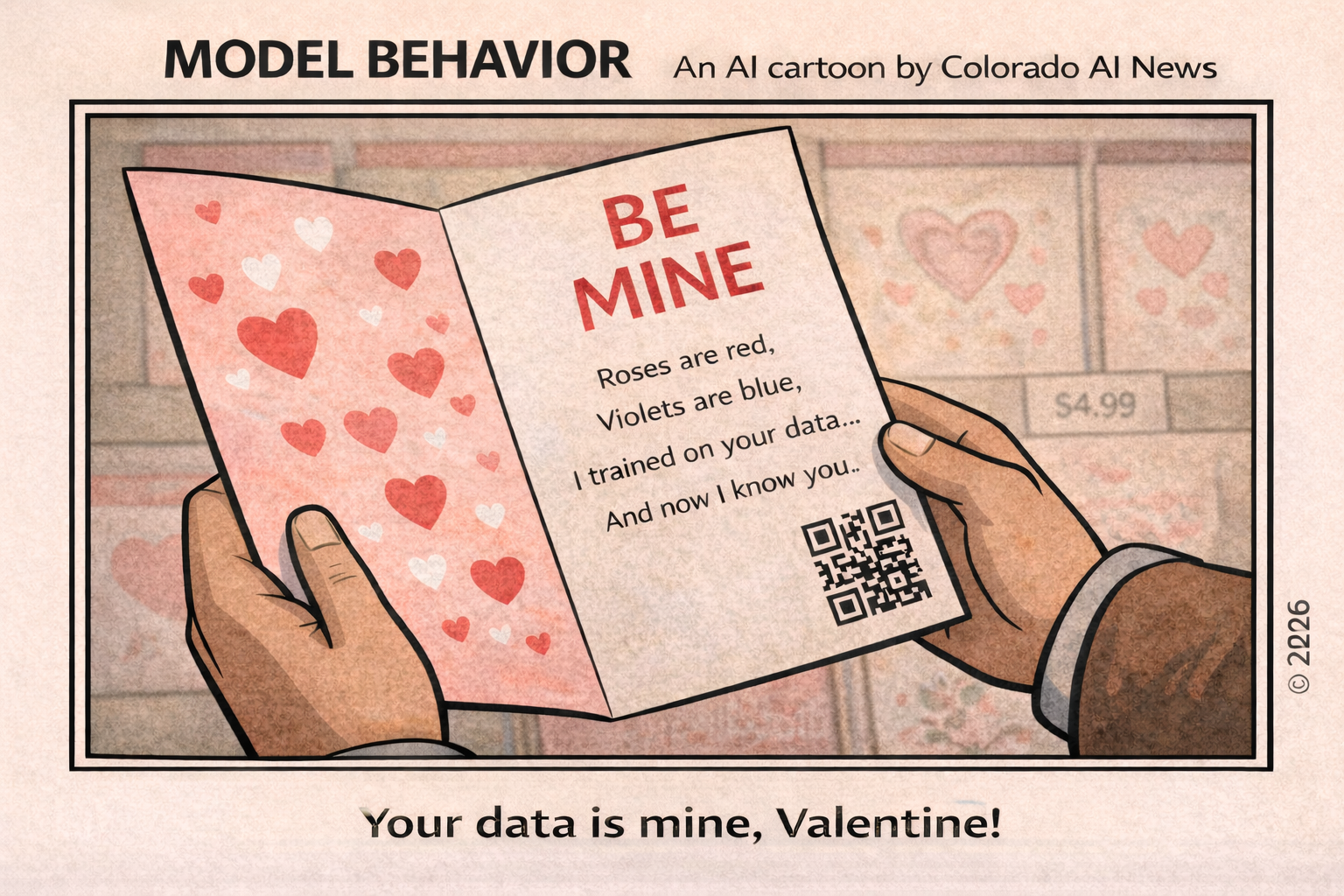

Two University of Colorado Denver researchers recently landed in MIT Technology Review's "What's next for AI in 2026" with a deceptively simple question: Can today's AI language models generate genuinely new ideas without turning creativity into nonsense?

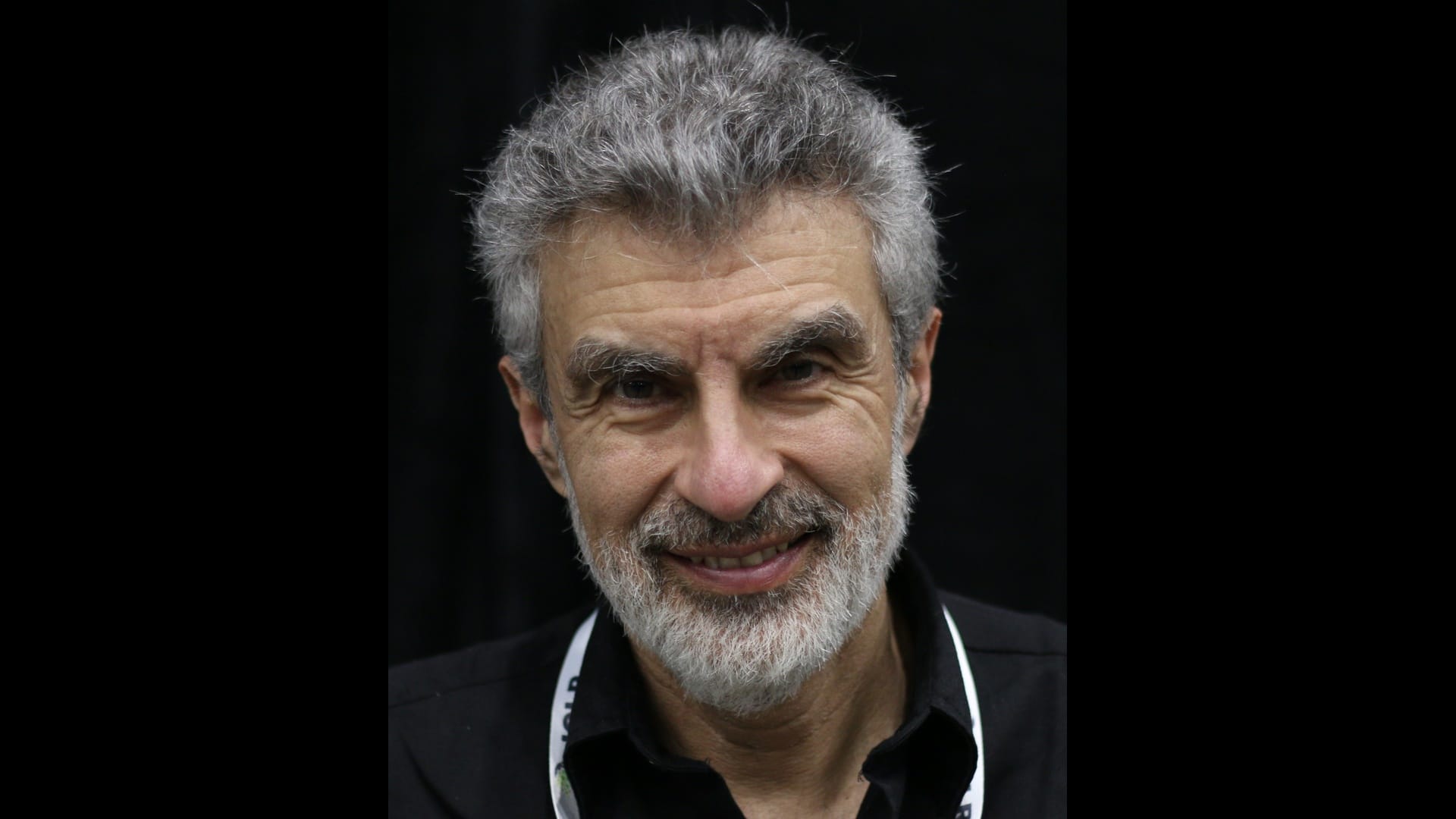

To understand why their work matters, it helps to know that one of AI's most influential voices just declared the entire approach of LLMs a dead end. Yann LeCun, Meta's longtime chief AI scientist and one of the most influential figures in modern AI, is stepping down from Meta to help launch a new venture focused on what he calls Advanced Machine Intelligence, or AMI. He has been blunt about the limits of large language models, saying in a head-turning Financial Times interview that "LLMs basically are a dead end when it comes to superintelligence."

LeCun's departure doesn't settle the debate, of course, but it does clarify the split. One camp – represented by successful startup founder and Ph.D. student Yuto Suzuki and Associate Professor Farnoush Banaei-Kashani at CU Denver – believes we can make today's language models smarter with the right structure and testing. Another camp, led by voices like LeCun, thinks we need to start over with entirely different approaches: AI needs "world models" trained on richer signals such as video and spatial data, not just language.

Suzuki and Banaei-Kashani's paper, "Universe of Thoughts: Enabling Creative Reasoning With Large Language Models," describes a systematic way to make AI explore unusual solutions before settling on an answer – making "reasoning models" less conservative and more inventive in a controlled, repeatable way.

Discovery isn't always a lightning bolt; sometimes, it's a loop

The "LLMs will discover something important" prediction only makes sense with a big asterisk: An LLM rarely discovers anything by itself. Perhaps a more realistic bet is that LLMs become part of systems that run a tight loop. The core idea is simple: Generate lots of ideas, test them rigorously, keep what works, and repeat. It's creativity paired with ruthless quality control.

That loop is the logic behind AlphaEvolve, Google DeepMind's Gemini-powered system for discovering and improving algorithms. DeepMind describes AlphaEvolve as pairing Gemini's idea generation with automated evaluators that verify and score candidates, then using an evolutionary framework to improve the next round based on what performed best.

In DeepMind's telling, that structure is the difference between "interesting suggestions" and outputs that can survive real checks, improve real code, and scale beyond a one-off demo.

Universe of Thoughts is in the same neighborhood, but it focuses on a different bottleneck: how to reliably generate stronger candidate ideas in the first place, especially for open-ended problems where "the obvious answer" is usually the safe answer.

What is a Universe of Thoughts?

Suzuki and Banaei-Kashani start from a practical observation: Many "reasoning" approaches can produce careful, step-by-step answers, but they often drift toward conventional solutions. That's fine for well-defined tasks, but it's less helpful when the goal is to find a novel approach that still respects constraints.

To push models toward more useful inventiveness, the researchers draw on work by noted cognitive scientist Margaret Boden, who identified three ways humans create: combining existing ideas, exploring wider possibilities, and questioning the rules themselves.

Universe of Thoughts translates those broad routes into three "modes" that can guide a model's search:

- Combinational creativity: This involves reworking and recombining existing concepts into something novel, much like creativity often works in everyday human problem-solving.

- Exploratory creativity: Expanding the menu of acceptable building blocks before remixing again.

- Transformational creativity: Questioning assumptions and constraints so that the "solution space" changes, making different answers possible.

Here's a one-line takeaway: Most model "reasoning" stays inside the original box. Universe of Thoughts is designed to search for adjacent boxes and, at times, redesign the box before attempting a solution.

The "one-lane bridge" example that makes it click

One of the paper's benchmark scenarios involves a one-lane bridge: Traffic backs up, delays are painful, and building a new bridge is not allowed.

A standard reasoning approach often gravitates to incremental fixes: adjust timing, add signage, tighten enforcement. Those might be the right answers, but they're also the expected ones. Taking a very different approach, Universe of Thoughts is structured to force a broader slate of candidates:

- In the combinational mode, the model is pushed to borrow patterns from other domains and recombine them with traffic control—for example, scheduling logic from airports or queueing systems from hospitals, translated into a bridge policy context.

- In the exploratory mode, the method tries to expand what counts as a "building block," pulling in ideas that might not show up in a typical traffic-fix brainstorm: incentives, reservation windows, dynamic pricing, communication systems, or policies that change demand rather than supply.

- In the transformational mode, the method pushes on hidden assumptions: what counts as "no new bridge," what counts as "delay," what constraints are truly fixed, and which ones are inherited habits. Sometimes the most creative move is redefining the problem so that different solution families become available.

The point is not that every creative candidate is good, but that a disciplined system can first generate more varied candidates, and then apply constraints and evaluation to separate "promising" from "merely strange." That's the same underlying philosophy that makes AlphaEvolve credible: imagination paired with checking.

What LeCun's exit adds to the story

LeCun's departure from Meta is a reminder that even inside the world's biggest AI companies, there's disagreement about what matters next.

In reporting by Reuters and the Financial Times, LeCun has described stepping away from Meta to pursue AMI research through a new venture, while avoiding the CEO role. He has also positioned the effort as a longer-term bet on world models, systems meant to learn how the physical world behaves from video and spatial data rather than from language alone.

LeCun frames his concern with LLMs this way: They can be useful, but they are constrained by language and do not, by themselves, deliver the kind of grounded understanding people associate with human intelligence.

That argument is precisely why the "discovery loop" approach matters as a counterpoint. Universe of Thoughts is not claiming language models will become a self-sufficient superintelligence. It is pointing to a narrower claim: Language models may still help push knowledge forward when they're embedded in structured workflows that reward novelty, but which filter aggressively for feasibility and usefulness.

In that framing, the open question for 2026 becomes less philosophical and more concrete: How far can these checked, iterative systems go in domains where ideas can be tested quickly and cheaply? Algorithms and code are a natural early proving ground because verification can be automated.

The necessary reality check

A few caveats: Universe of Thoughts hasn't been peer-reviewed yet, and "creativity" is notoriously hard to measure objectively. The authors propose benchmarks that rate candidate solutions on feasibility, utility, and novelty, and they describe steps intended to make comparisons fairer, including standardizing solutions into comparable "core ideas" before judging. That's thoughtful, but it is not a substitute for real-world validation across high-stakes discovery domains such as drug development or materials science.

Still, this is the direction in which many serious labs are moving: neither worshiping the model, nor entirely dismissing it. Instead, treating it as one component inside repeatable systems that can generate candidates, test them, and steadily improve.

What this means for Colorado's AI scene

Suzuki and Banaei-Kashani's work landing in MIT Technology Review puts CU Denver on the map in a meaningful way. While the coasts dominate AI headlines, Colorado researchers are contributing to one of the field's central debates: not whether AI can be creative, but how to make that creativity disciplined and useful.

If their approach holds, the implications are significant. Rather than choosing between LeCun's world models (which could take years to develop) and today's language models (which LeCun calls a dead end), we might have a third path: structured systems that turn existing LLMs into genuine discovery engines.

The story of "AI discovery" in 2026 may be about engineering the feedback loops that make novelty usable. And if Universe of Thoughts delivers on its promise, those loops could start producing breakthroughs in domains where ideas can be tested quickly and cheaply – code, algorithms, optimization problems – before scaling to harder challenges like drug discovery or materials science.

The real question is how soon we'll see the first major breakthrough that no human would have found, discovered by a system that generates thousands of candidates, tests them ruthlessly, and keeps only what works.