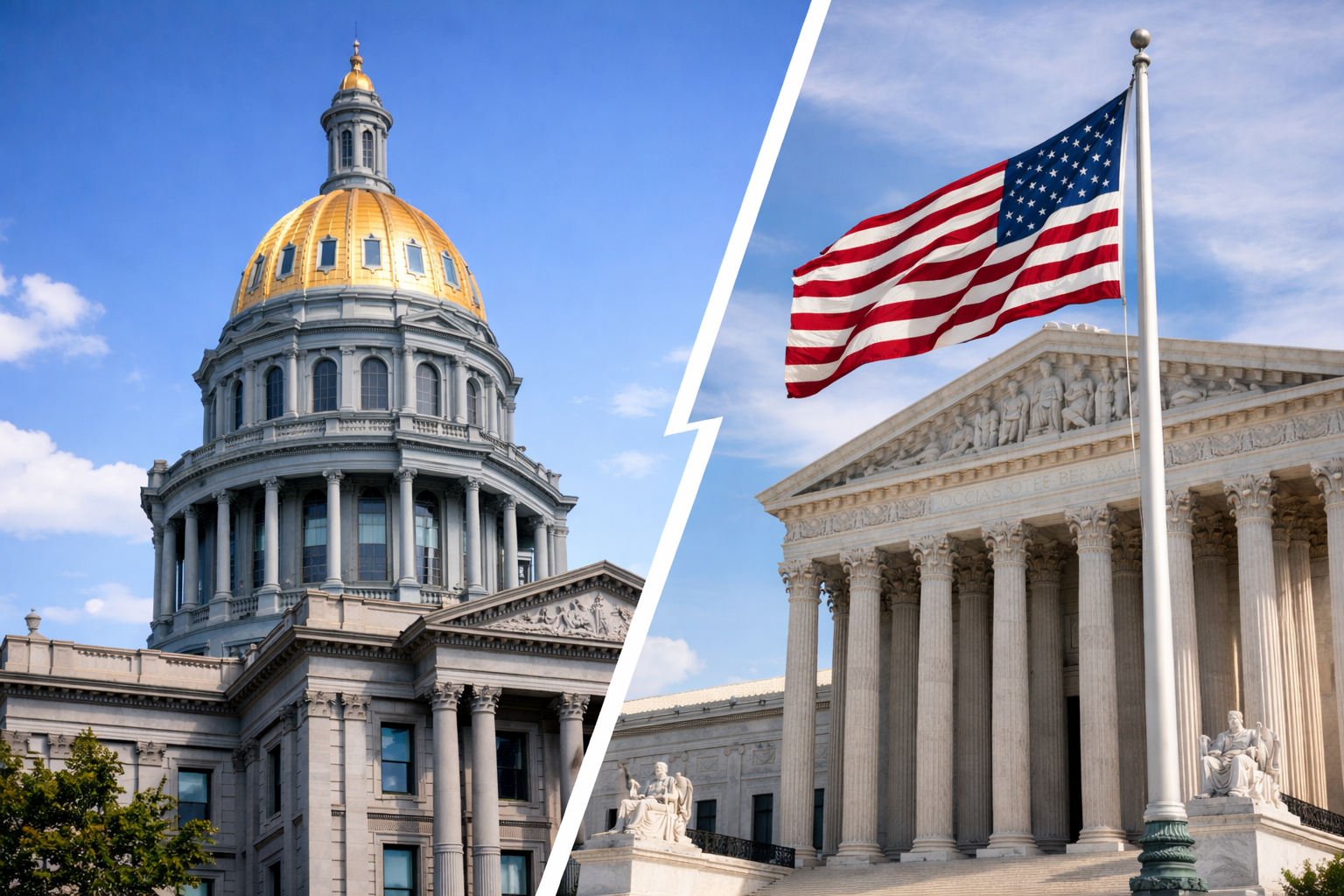

Colorado officials and lawmakers are signaling that President Trump's new executive order aimed at state AI laws won't scare them off. If anything, it's speeding up an effort already underway at the state Capitol: Rewrite the 2024 law to make it more workable for businesses, while keeping the consumer protections that motivated it in the first place.

That's the political fight. The legal fight is looming right behind it. Legal analysts have raised questions about the executive order's strategy, especially the idea of using broadband grant leverage to shape state AI policy, suggesting it could be vulnerable to court challenges on separation-of-powers grounds.

What Trump's order actually does

The executive order, published by the White House on Dec. 11, sets a national posture: AI should be governed through a "minimally burdensome" federal framework, not what it calls a fragmented state-by-state patchwork.

Then it points federal agencies at a few concrete moves:

- It directs the attorney general to stand up an AI Litigation Task Force and challenge state AI laws that the administration considers inconsistent with federal policy.

- It directs the Commerce Department to publish within 90 days an evaluation of state AI laws it views as "onerous."

- It tees up restrictions on certain federal funds, including parts of the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program, commonly called BEAD, tied to state AI policy choices.

The order also appears to reference Colorado's law by arguing that banning "algorithmic discrimination" could force "false results" to avoid differential impact on protected groups.

What Colorado's AI law does, in plain English

Colorado's 2024 law, SB24-205, focuses on "high-risk" AI used in consequential decisions like employment, housing, lending, health care, legal services, and other high-stakes areas. It imposes duties on both developers and deployers to use "reasonable care" to prevent algorithmic discrimination, with disclosures and risk management expectations.

It also hasn't taken effect yet. After a special session, lawmakers delayed the compliance start date from Feb. 1, 2026, to June 30, 2026 via SB25B-004.

That delay matters now because it creates a runway: Colorado can try to "fix" the law in the four-month long 2026 legislative session while the federal order ramps up its review-and-litigation machinery.

The money hook: broadband funding is real - and it's real money

Trump's order gestures at BEAD as a pressure point. In Colorado, that's not theoretical.

On Dec. 2, the Polis administration announced the federal government approved Colorado's plan for $421 million in BEAD funding to expand broadband access, especially in rural parts of the state. An additional $400 million is expected down the road.

So, when the order talks about conditions and eligibility for certain BEAD funds, it lands on a visible, concrete, and sizable pot of money tied to one of Colorado's core infrastructure goals.

That's one reason this story plays well beyond the policy crowd. It mixes AI regulation, federalism, and a dollars-and-cents question many Coloradans can understand: "Could this mess with massive funding for rural internet buildout?"

Colorado's public posture: Revise, don't retreat

Axios Denver reported that Colorado leaders are pushing toward consensus changes rather than repealing the law under federal pressure, with Gov. Jared Polis continuing to argue for a national framework, while also backing a Colorado rewrite in 2026.

Additionally, Colorado Public Radio reported that the Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser has said the state would challenge federal threats in court and has pushed lawmakers to improve the law, but not abandon it.

On December 21, the Denver Post indicated that Weiser argued the president lacks "free-standing authority" to punish states for laws he dislikes, and he suggested Colorado would be ready to fight if federal funding is used as a weapon.

State Rep. Brianna Titone, who, as previously reported in Colorado AI News, has been a key proponent of anti-discrimination protections, framed the executive order as more "wish list" than law, according to that same Denver Post coverage.

The legal question: can an executive order really swat down state AI laws?

Here's where the legal uncertainty becomes central. Axios' legal analysis, along with reporting by Reuters, lay out potential vulnerabilities that experts have identified:

- Separation of powers: A U.S. president may lack the authority to override state laws without clear congressional grounding.

- Dormant Commerce Clause: The order leans on an aggressive interpretation of interstate commerce limits, but legal observers have noted that the doctrine typically turns on whether a state is discriminating against out-of-state interests, not simply regulating consumer protection.

- Spending Clause issues: Conditioning unrelated federal funds to coerce state policy changes is legally fraught, especially if Congress did not authorize that linkage.

In other words, even if the administration can make life difficult for states in the short term through agency action, the broad claim that Washington can unilaterally freeze state AI regulation may be where the order could face its strongest legal challenges.

What happens next: January 14 in Denver - and a longer road in court

Colorado's regular 2026 legislative session begins on January 14, which is when the rewrite efforts are likely to take shape as actual bill language.

At the same time, the White House order sets a clock for federal action: The AI Litigation Task Force is supposed to be established within 30 days, and the Department of Commerce is supposed to publish its evaluation of state AI laws within 90 days.

That means Colorado businesses, especially companies that build or deploy AI in high-stakes contexts, are forced to plan under significant uncertainty from two directions: what changes the state legislature happens to make, and what the federal government chooses to target.

The dinner-table question

Colorado's AI law started as a consumer protection story: Don't let automated systems quietly discriminate in hiring, housing, credit, or other high-stakes areas. Trump's executive order reframes it as a national competitiveness story: Don't let states slow the AI race with red tape.

So here's the question worth arguing about over roast beast and plum duff: Do we want one national AI rulebook even if it's looser, or do we want states experimenting with protections that may be stronger but messier for companies to have to comply with?